I started talking about world music in the ‘40s, but no one knew what I was talking about. Of course, with today’s globalization, it’s hard to believe it caused the problems it did back then. But the unfamiliar and challenging time signatures caused a lot of people to shy away from it. I knew then that jazz people weren’t listening to what was coming out of Africa, so I tried to familiarize various musicians with the music. “My interest in African music was piqued after hearing about Dennis Roosevelt’s expedition into the Belgian Congo in the mid-40s. Why are you condemning Dave for experimenting with this when he’s on the right track?’ I couldn’t have asked for a better endorsement. When he finished, he asked if anybody knew what time signature he had just sung in. A black doctor in the crowd named Willis James stood up and started singing in some African tribal language. Some of them said I shouldn’t play jazz in these odd time signatures. ‘You can’t play jazz in 5/4.’ In fact, at the time, there was a meeting of some excellent musicians like members of the Modern Jazz Quartet, Ornette Coleman, Gunther Schuller and others discussing various musical matters.

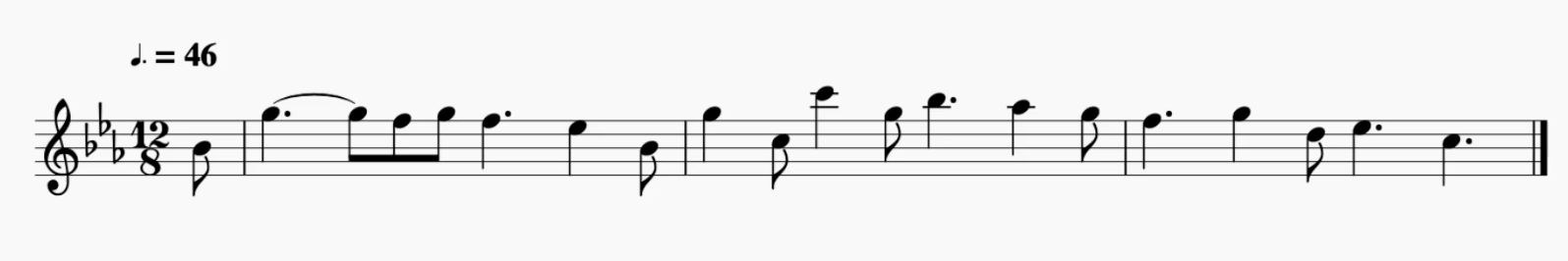

Locally, a few jazz snobs got impatient with me. “When Take Five first came out, many guys were fantastic musicians who couldn’t play it. All of this in a concise, 38-minute LP.ĭecades later, Brubeck said this to me in an interview: Everybody’s Jumpin’ and Pick Up Sticks are situated in a 6/4 rhythm zone. In Three to Get Ready, Brubeck alternates between 3/4 and 4/4. Blue Rondo à la Turk - which Brubeck wrote after hearing a group of street musicians playing a traditional Turkish folk song in 9/8 during a tour of Eurasia - starts in 9/8, swings to 4/4, then fluctuates between Turkish and western rhythms. Time Out is all about experiments with time. (Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue is still the top-selling jazz album of all time, surpassing four times platinum.) In 2011, the RIAA certified it at more than 2 million sales worldwide. It was the first jazz album to sell more than a million copies. Take Five was the centrepiece of Brubeck’s top-selling jazz recording, Time Out. Hours later, in my troubled mind, I still thought I could still be sentenced to jazz prison, charged with “botched time.” We had little understanding that most folks watching at home through those Admiral televisions were more focused on getting a receptive black-and-white picture, not “junior jazz” time. The episode is one Wayne and I talk about to this day. At song’s end, we are clapped off and praised as if we were child prodigies. He looked as if he’d been struck by an oncoming bus. What if viewers catch me fumble or falter? I’m too young to die on live TV. From the corner of an eye, I could see cameras glide about the room and one of them close in on my hands. I then try to cram Paul Desmond’s beautiful melody into four-bar sequences, to no avail. I glance over at the drummer and notice he’s swinging a metre of his choosing - one fit for a perky dance band. Suddenly, the brothers find themselves in the weirdest bandstand crossfire imaginable, trying to squeeze melody and rhythm into a squared beat. Beats one to four drop in sequence, but never beat five. Take it, boys.” I count the tempo in, and the quartet hits the downbeat spot on. “Ladies and gentlemen, all the way from across the Ohio River from Jeffersonville, Indiana, to perform for you the Dave Brubeck Quartet’s hit recording, Take Five… the King brothers. We shuffled our way through rehearsal and then moved on to the main event. Wayne played alto sax, and I played the piano.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)